There’s a conversation I’ve had with project managers many times over the decades. It usually starts when an ask for time in the plan to either source realistic test data or build a tool that generates it. The response is typically some variation of “we haven’t got budget for that, just start development.”

The outcome is predictable. The developer complies. They work with placeholder data and make assumptions about what production conditions will look like. Sometimes those assumptions are correct. Often they aren’t, and the problems surface later when they’re more expensive to fix.

The Test Data Problem

Software that works perfectly with three test records behaves differently with three thousand, differently again with three hundred thousand, and differently still with three million. But representative data isn’t just about volume. It’s about variation. Real-world data has edge cases, inconsistent formats, accumulated history, and unexpected relationships between records. An email client feature developed against a handful of synthetic messages fails to account for the conversation threading, attachment variations, and folder structures found in a fifteen-year-old production mailbox. The gap between placeholder data and production reality creates blind spots that only become visible after deployment.

This isn’t just anecdotal observation. The research on this is unambiguous. Google’s DevOps Research and Assessment (DORA) team identifies test data management as a core capability for high-performing software teams. Their findings indicate that adequate test data must be available on demand, and that it must not constrain the tests teams can run. A 2021 study by Garden found that developers lose approximately 39% of their work week to tasks related to environment and data provisioning, estimating the annual cost to U.S. companies at $61 billion spent on these frustrations rather than actual innovation.

The traditional solutions each have drawbacks. Production data copies introduce privacy and security concerns. Manual data creation is time-consuming and rarely comprehensive. External dependencies create bottlenecks and delays.

A Personal Case Study

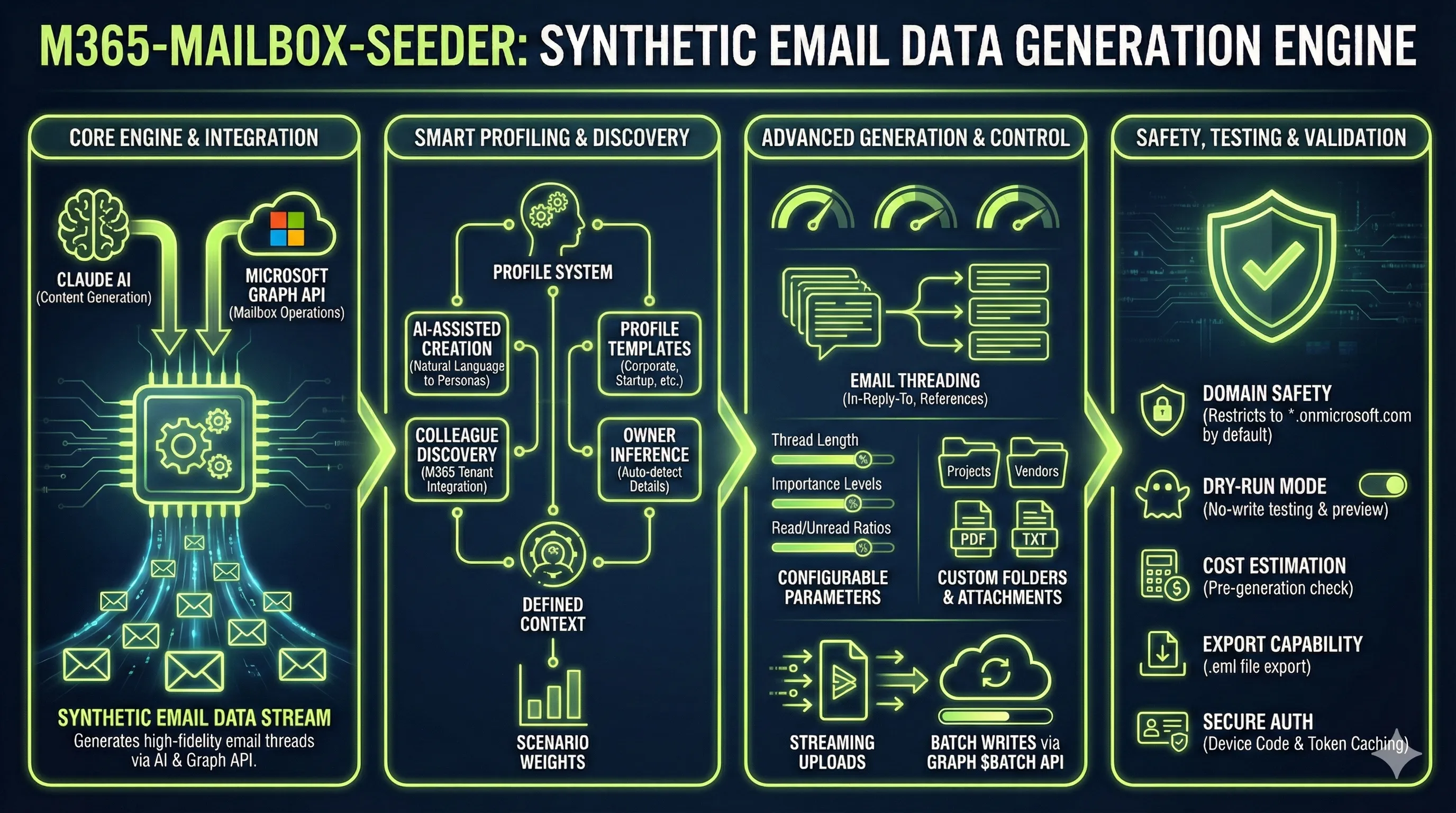

I recently built a tool called m365-mailbox-seeder to address this problem for Microsoft 365 mailbox testing. The tool generates synthetic email data in M365 developer sandboxes, complete with realistic email threads, attachments, folder structures, and conversation flows. I built it using an AI coding agent, which shaped both the development process and some of the design decisions in ways worth examining.

Working with a Coding Agent

For those unfamiliar with the term, a coding agent is an AI system that can write, modify, and test code based on natural language descriptions. Unlike simple code completion, these agents can reason about requirements, make architectural decisions, and iterate on implementations based on feedback. Think of them as a highly knowledgeable collaborator who types very fast but needs clear direction.

I used Cursor (an AI-enhanced development environment) as my primary interface, describing functionality requirements conversationally rather than writing detailed specifications upfront. The development process wasn’t traditional spec-driven development. It was closer to having an ongoing dialogue with a capable developer who happened to be artificial.

The experience sits somewhere on a spectrum. At one end is what some call “vibe coding,” where developers accept AI-generated code with minimal review. At the other end is traditional hand-coding where every line is deliberate. My approach fell somewhere in between. I scrutinized code incrementally as it was generated, understood the architectural decisions being made, and course-corrected when needed.

What Worked

The tool successfully generates realistic email content using Claude (Anthropic’s AI model) combined with Microsoft Graph API for writing to mailboxes. It supports configurable personas, scenario templates, email thread headers (In-Reply-To, References), attachment generation, and folder distribution. The profile system allows defining organizational contexts, from startup environments to enterprise hierarchies.

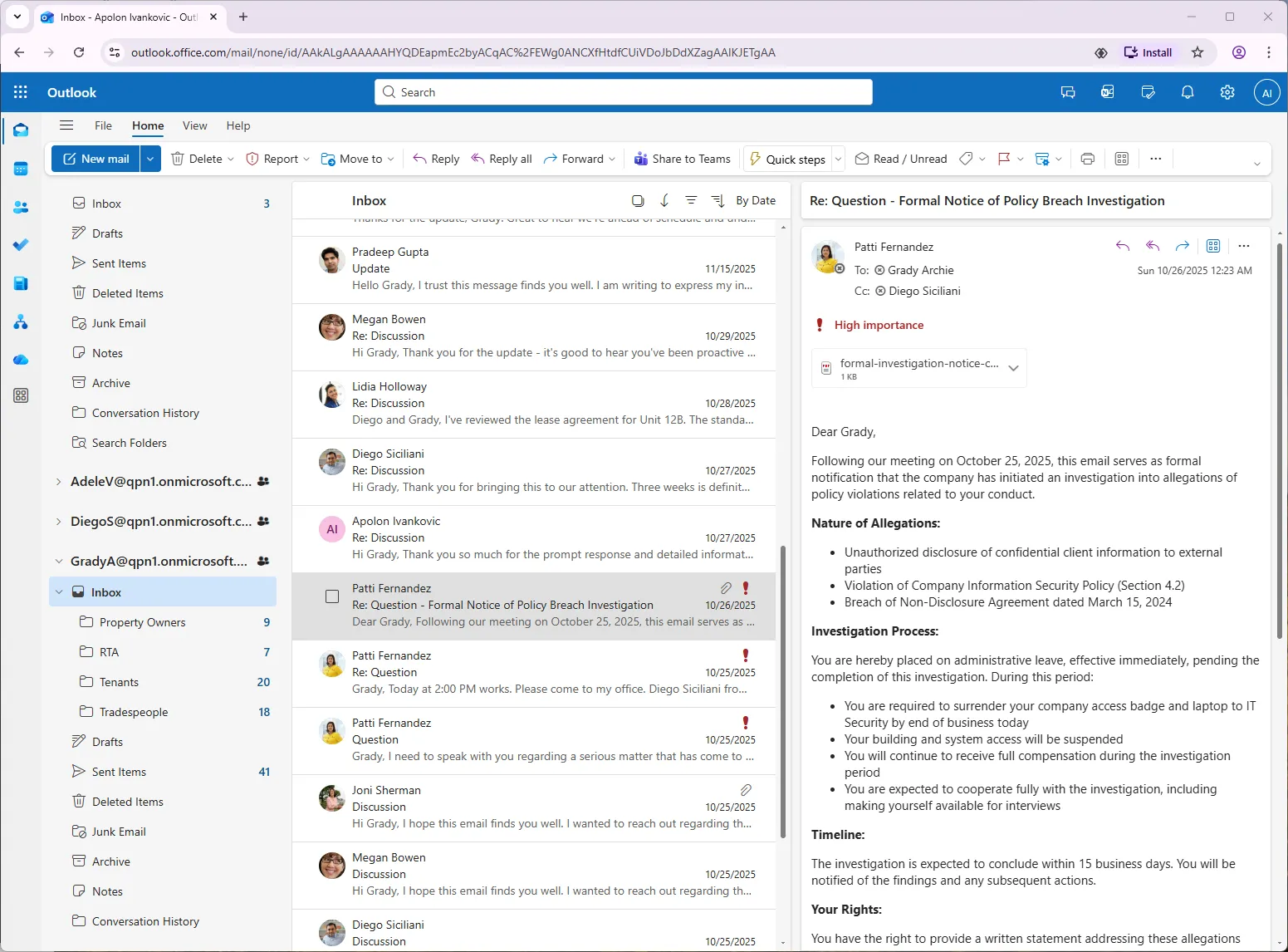

The generated data proved valuable for developing a subsequent application that synchronises Outlook mailboxes to local Markdown files. Having a populated test mailbox with varied content exposed edge cases that placeholder data would have missed entirely.

What I Would Reconsider

I used this tool to supply test data during early development of a Microsoft 365 Mailbox Mirror application. It was genuinely helpful for getting started, but the experience revealed several limitations in the approach of using AI to generate each individual email.

Cost accumulation. Each execution costs between $3 and $10 depending on volume. For a personal project this is manageable (and annoying), but it discourages generating the larger datasets that would be most representative of production conditions.

Speed constraints. LLM output generation is slower than expected. The asymmetry between input and output tokens (reminiscent of ADSL’s downstream versus upstream bandwidth disparity) means that while context can be large, the actual content generation is rate-limited. Even cheaper, faster models like Claude Haiku didn’t significantly improve throughput for bulk content generation, and Haiku’s reduced output token budget limited how much content could be generated per request.

Diminishing variation returns. After generating several hundred emails, the thematic variation plateaus. The AI produces competent content, but the diversity doesn’t scale linearly with volume.

Structural authenticity. As the Mailbox Mirror project progressed, I received feedback that the variation in HTML structure found in real-world emails just wasn’t reproducible in the synthetic equivalent. Different email clients, different eras of Outlook, forwarded chains with mixed formatting, signatures with embedded images, calendar invites, and delivery receipts all produce structural quirks that synthetic generation doesn’t anticipate.

For generating large volumes of test data, a more cost-effective architecture would use AI to create a substantial library of templates, perhaps several dozen per scenario type, with parameterised slots for names, dates, specific details, and action items. The actual email generation would then be deterministic, randomly selecting and populating templates without incurring per-email AI costs. The creative intelligence would be front-loaded into template design rather than distributed across every generation.

But there’s a second category of test data tooling worth considering. Even with better architecture, I don’t think synthetic generation without some influence from production data will ever get you 100% of the way there. The edge cases and accumulated variation in real-world data are things you can’t anticipate until you’ve seen them. This is where anonymisation comes in as a complementary approach. Anonymisation is still synthetic data tooling, but with production data as the input rather than prompts or templates. The output can’t be traced back to real individuals, but it preserves structural quirks that pure generation misses.

Building an anonymisation tool is a different challenge, though. The focus shifts from creating realistic content to ensuring secure chain of custody throughout the transformation. Who has access to the original data, where the transformation happens, how you verify that no identifying information leaks through, and how you audit the process all become primary concerns.

The Broader Principle

This experience reinforced something I’ve observed throughout my career in industrial software and enterprise development. Investing in representative test data infrastructure is generally worth more than the initial effort suggests.

Enterprise vendors publish case studies that quantify these benefits. Mizuho Securities reported a 90% reduction in test data delivery time and $700,000 in annual labour savings. ING Belgium achieved 100x improvement in test coverage using synthetic data generation. These are marketing materials for expensive enterprise platforms, and they read like it. But the underlying point stands. Organizations that invest in test data infrastructure see measurable returns. The difference now is that you don’t necessarily need an enterprise vendor to get there. Coding agents make it feasible to build fit-for-purpose test data tools yourself.

The pattern holds whether you’re building SCADA systems, enterprise integrations, or email processing applications. When I worked on industrial software requiring integration with external systems that couldn’t be accessed due to security constraints, implementing realistic service stubs was consistently worth the investment. Project managers often resist this work because it doesn’t visibly progress toward the delivery milestone. But across the full project lifecycle, including maintenance, the time saved in debugging, the defects avoided in production, and the confidence gained during development more than justify the upfront effort.

Coding Agents as Tool Builders

Coding agents are well-suited to building utilities, scaffolding, and infrastructure tooling. The m365-mailbox-seeder took days to develop rather than weeks, despite incorporating Microsoft Graph API integration, Azure AD authentication, structured AI prompting, and a reasonably sophisticated profile system. A developer working alone without AI assistance would have spent considerably longer on the same functionality.

This changes the economics. Test data generators, service stubs, and simulation tools that were previously deemed too expensive to build become viable when development time compresses by a factor of three or more.

The investment calculation changes from “is this tool worth three weeks of developer time?” to “is this tool worth three days of developer time plus some AI costs?” For infrastructure that will be used throughout a project’s development and maintenance lifecycle, that calculation often works out favourably.

Considerations for Implementation

A few observations from this project that may apply more broadly.

Start with bounded scope. Test data generators and simulation tools are excellent candidates for AI-assisted development because they have clear success criteria (the data either works for testing or it doesn’t) and limited integration surface area. Enterprise features with complex business rules and extensive integration points require more careful oversight.

Factor in ongoing costs. Tools that use AI at runtime, like my email generator, accumulate costs with each use. Tools that use AI only during development have fixed costs regardless of how often they’re subsequently used. The latter pattern is generally preferable for infrastructure intended for long-term use.

The verification loop matters. Coding agents perform best when they can test their own outputs. Providing access to realistic test environments, even incomplete ones, improves the quality of generated code. There’s a reinforcing effect here. Better test infrastructure enables better AI-assisted development, which can in turn produce better test infrastructure.

The M365 Developer Sandbox

For teams working with Microsoft 365, the Developer Program provides a useful testing foundation. It offers free, renewable E5 subscriptions with 25 user licenses specifically for development purposes. The instant sandbox option includes pre-configured users and sample data, reducing setup time from days to minutes. Whether you use a tool like m365-mailbox-seeder, build your own, or take an entirely different approach, the sandbox provides a safe environment to populate with representative test data.

The broader point stands regardless of platform. Budget allocated to test data tooling isn’t being diverted from feature development. It’s removing a constraint that would otherwise slow every subsequent feature across the entire project timeline.

There’s a lot of untapped potential in the Microsoft Graph APIs for automating business operations, both through traditional deterministic automation and through AI agent-based approaches. If you’re looking to explore what’s possible for your organization, get in touch.