If you’ve used ChatGPT or Claude, you’ve probably noticed something odd. Ask the same question twice, and you get different answers. Not wildly different, but different enough to make you wonder: is this thing just guessing?

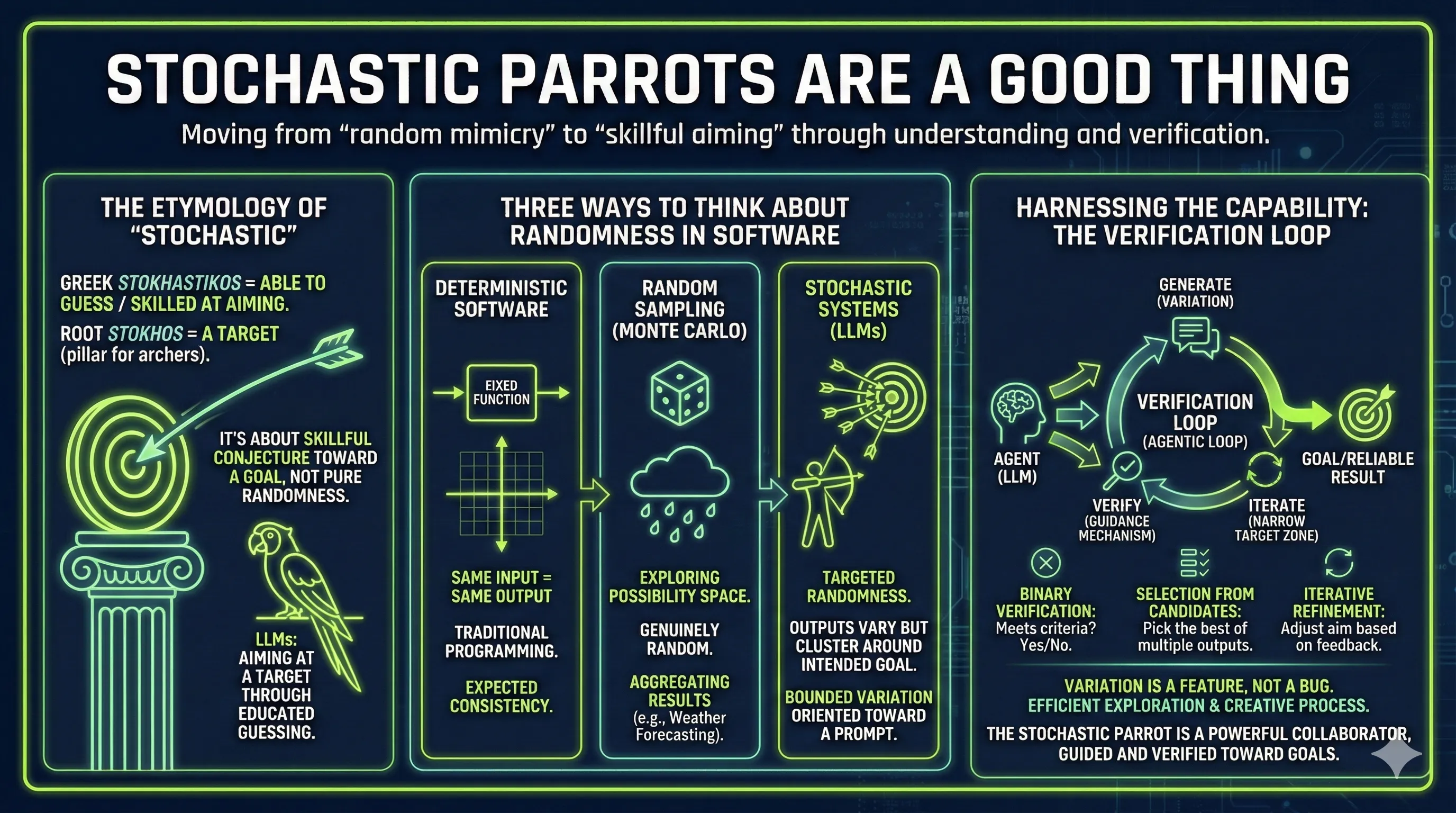

That question led me to dig into a term critics use to dismiss these systems: “stochastic parrot.” The phrase suggests LLMs are just mimicking text without understanding, producing random outputs based on statistical patterns. But when I looked up what “stochastic” actually means, I realized the critics might have accidentally given LLMs a compliment.

For a while, I avoided using the word “stochastic” entirely. The term “stochastic parrot” had been deployed so effectively to denigrate LLM capabilities that the word felt tainted. Instead, I started describing these systems as “probabilistic”. But that never quite fit either. Probabilistic felt too passive, too much about mere chance. It didn’t capture what I was observing when working with these models. That dissatisfaction led me to look up the actual etymology of stochastic, which ultimately led to this post.

The Etymology That Changed My Thinking

The word “stochastic” comes from the Greek stokhastikos, meaning “able to guess” or “skilled at aiming.” The root word stokhos literally means “a target.” Specifically, it referred to an erected pillar for archers to shoot at. The original sense was about skillful conjecture toward a goal, not pure randomness.

So when someone says “stochastic parrot,” they’re actually describing something that aims at a target through educated guessing. That sounds less like a criticism and more like a useful capability.

This maps to what you see when you use these systems. Ask ChatGPT for a summary of an article twice, and you get two different summaries. But they both capture the main points. The wording varies, but both answers cluster around the same meaning. That’s the archer hitting near the bullseye, not the same spot every time, but also not shooting randomly into the forest.

Three Ways to Think About Randomness in Software

This distinction matters when you’re trying to understand how AI systems work and why they behave the way they do. There are three different approaches to randomness in software, and conflating them leads to confusion.

Deterministic Software is what we’re used to. Same input, same output, every time. If you run a function with the same parameters, you get identical results. This is the world of traditional programming, and it’s what most people expect from software.

Random Sampling embraces pure randomness as a problem-solving strategy. Weather forecasting works this way. When you can’t calculate an exact outcome, you run thousands of simulations with random variations and see what patterns emerge. In computing, this approach is called a Monte Carlo method, named after the famous casino. It’s genuinely random. You’re not aiming at anything specific. You’re exploring possibility space and aggregating results.

Stochastic Systems are different. They have randomness, yes, but that randomness is targeted. The outputs vary, but they cluster around an intended goal.

LLMs Are Stochastic, Not Just Probabilistic

This is the distinction that clicked for me. Large language models aren’t randomly sampling from all possible text. They’re stochastic systems. They produce varying outputs, but those outputs are aimed at something. Given a well-crafted prompt, the variation happens within a bounded space oriented toward a goal.

And here’s what makes this powerful. As models improve, the bounds of that targeting get smaller. Better models understand intent more precisely. The archer’s grouping gets tighter. You’re still not getting deterministic output, but you’re getting increasingly constrained variation around what you actually wanted.

This is why verification loops matter. When you chat with ChatGPT, you’re having a conversation. But increasingly, AI systems are being built as agents: software that takes multiple autonomous steps toward a goal rather than waiting for you to prompt each action. When an agent works toward a goal, checking its work along the way, each verification cycle narrows the target zone. The prompt alone doesn’t fully define the target. The feedback loop does.

The Verification Loop Makes It Work

I already understood the importance of verification loops, but reading Anthropic’s article on evaluating AI agents reinforced that understanding. Anthropic builds Claude, and their engineering team has formalized this pattern: the AI produces something, then graders verify whether it hit the target. Those graders can be deterministic code, another LLM, or a human. Seeing it spelled out made clear just how central verification is to making stochastic systems reliable.

If you view the agent as purely random, this seems like a desperate attempt to wrangle chaos. But if you understand the agent as stochastic, then verification becomes a guidance mechanism. This generate-verify-iterate cycle is one form of what developers call an agentic loop, a broader pattern where AI agents autonomously perceive, reason, act, and observe in continuous cycles toward a goal. It’s not about controlling randomness. It’s about iterating toward the goal.

This iterative approach only becomes practical once large language models reach a certain capability threshold where their targeting is reasonably well-aligned with intent. Earlier models scattered too widely for iteration to be efficient. Current models are close enough that each iteration reduces the error distance from a goal that is either well-defined upfront or discovered through the iteration process itself.

The verification loop can work in different ways.

- Binary verification checks whether the output met the criteria. If not, try again.

- Selection from candidates generates five outputs, all potentially correct, and picks the best one.

- Iterative refinement recognizes the output is close but not quite right, then provides feedback to adjust the aim.

This is exactly how human expertise works in many domains. A designer produces multiple concepts, then selects the best one. A writer drafts, revises, and edits. An architect explores options before committing. The variation isn’t a weakness. It’s the exploration phase of the creative process.

Why This Matters for Your Frustration

If you’ve been frustrated with LLMs because they don’t give you the same answer twice, or because they occasionally make things up, I get it. We’re conditioned by decades of deterministic software. You expect consistency because that’s what computers have always given us.

But consider this. The stochastic nature of LLMs isn’t a limitation to be fixed. It’s a capability to be harnessed. The key is building the right verification mechanisms.

The right verification loop transforms stochastic output into something you can rely on. Not deterministic, but consistent enough to be incredibly useful. Generate multiple options, validate against criteria, pick the best one. The variation becomes an asset. You’re exploring the solution space efficiently, surfacing ideas you wouldn’t have considered, and converging on results that work.

The pattern emerging in AI development follows this structure. Let the stochastic system generate, then verify, then iterate. It’s the same pattern random sampling uses, but with targeted generation rather than blind exploration.

The Stochastic Parrot Is Actually Useful

So when I hear “stochastic parrot” now, I don’t hear criticism. I hear a description of a system that can be guided, verified, and iterated toward goals.

The parrot isn’t just randomly repeating words. It’s constrained by its training, responsive to prompts. And with the right verification loop around it, that stochastic parrot becomes a powerful collaborator.

The frustration comes from expecting determinism from a stochastic system. But once you understand its nature and build appropriate verification mechanisms, the variation transforms from a bug into a feature. You’re not fighting the randomness. You’re working with an archer who’s genuinely aiming at your target.