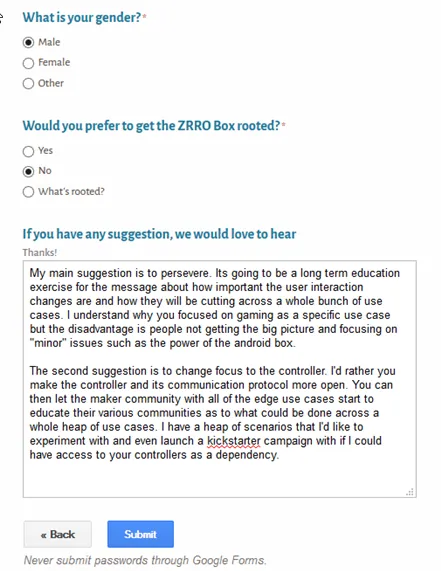

May 2015 brought significant progress in combining eye gaze tracking with visual touch interaction, exploring how these complementary input modalities could work together to create more natural and accurate user interfaces.

Tobii EyeX Evaluation

The Tobii EyeX eye tracking device arrived and was set up for experimentation. Compared to the EyeTribe device tested earlier, the Tobii hardware provided a noticeably better user experience—more reliable calibration, smoother tracking, and better SDK documentation.

However, a critical incompatibility emerged when attempting to use the Tobii eye tracker simultaneously with the Intel RealSense depth camera. The devices interfered with each other, causing hand sensing failures in the RealSense system. Both relied on infrared illumination and sensing, creating mutual interference that would require careful system design to resolve.

![]()

Eye Gaze Behavior Analysis

Using Camtasia and a standard webcam, eye gaze activity during normal mouse interaction was recorded and analyzed. This experimentation revealed patterns in how gaze preceded mouse movement—users looked at targets before moving the cursor there. Understanding these natural behaviors informed thinking about how visual touch interfaces augmented with eye gaze could feel more responsive than either technology alone.

The concept crystallized: eye gaze identifies regions of interest quickly (though imprecisely), while visual touch provides accurate interaction points within those regions. Together, they could overcome the fundamental accuracy limitations each faced independently.

Patent Landscape Research

Thorough analysis of Tobii and EyeTribe patent portfolios revealed the competitive landscape for multimodal interaction technologies. Tobii had already explored directions combining gaze tracking with other input modalities to achieve accuracy beyond what gaze alone provided. While their patents covered general multimodal approaches, the specific visual touch integration appeared unclaimed.

Research into Fujitsu’s iris scanning technology and eye gaze tracking work provided additional competitive intelligence. The challenge wasn’t technical feasibility—multiple companies were pursuing similar goals—but rather finding novel combinations and applications not already covered by existing patents.

Concept Document Evolution

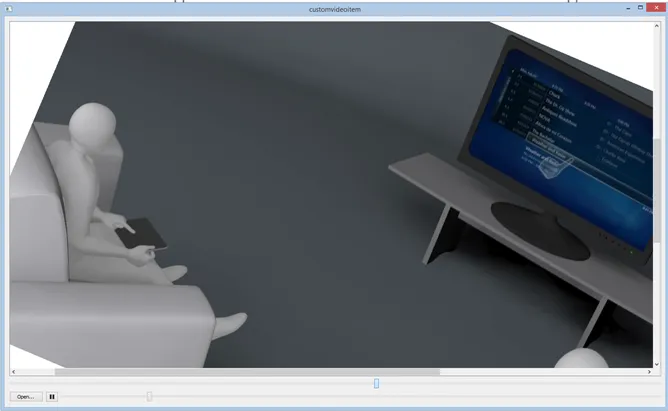

Significant effort went into consolidating notes and ideas from the previous six months into a coherent design document for augmented TV concepts. The document evolved to encompass:

- Visual touch offset approach for thumb-based interaction on large-screen phones (phablets)

- General architecture supporting N audiovisual devices, N augmenters, N displays, and N input surfaces in a room with N people

- Retrofitting visual touch UI for existing audiovisual devices through augmentation layers

- Eye gaze combined with visual touch for enhanced region-of-interest interaction

Design Drawing Development

Mockups were created for design drawings covering various visual touch scenarios and use cases. These drawings needed to communicate complex interaction concepts visually for patent applications, technical documentation, and potential partner presentations. A summary document was prepared for submission to a graphic artist to produce professional renderings.

Culling less commercially viable concepts from the documentation forced prioritization—which ideas offered the clearest paths to market, and which represented interesting research directions that should be deferred. This editing process brought focus to what could realistically be developed and commercialized with limited resources.

Google Project Soli Research

Google’s announcement of Project Soli—using radar for gesture recognition—prompted immediate investigation. The technology could potentially serve as an input mechanism for visual touch remote concepts. An innovative approach emerged: using visual touch data as a calibration mechanism for the radar’s machine learning pipeline, combining the strengths of both sensing technologies.

The insight was that visual touch provides ground truth data about hand and finger positions that could train radar-based gesture recognition systems. This represented a potential integration pathway between visual touch concepts and Google’s emerging interaction technology.

Trademark Challenges

Discussions with patent attorneys revealed that “Visual Touchscreens” and variations like “Vizual Touch” were likely untrademarkable—too descriptive of the actual functionality. Simply swapping letters (S for Z) proved insufficient for trademark protection. The recommendation was to develop a distinct brand name with “visual touch” as a tagline.

This legal reality forced thinking about branding strategy separately from technical terminology. The technology could be described as “visual touch” without that phrase serving as the company or product brand.

The month demonstrated progress toward a comprehensive multimodal interaction vision: eye gaze for rapid region identification combined with visual touch for precise interaction, potentially augmented with radar-based gesture recognition. Each technology complemented the others’ limitations, suggesting a path toward more natural and accurate interfaces than any single approach could provide.